In 2021 there were approximately 2,000 Ukrainians in Ireland; between early 2022 and September 2023 approximately 96,000 Ukrainians arrived in Ireland. As of June 2024, total arrivals were 107,000, of whom probably around 80% are still in Ireland. Although government policy aims to integrate Ukrainians fully into the labour market, data from the CSO, as well as surveys carried out by Ukrainian Action, suggest that only around 25% of all working age Ukrainians are actually employed. What went wrong?

Ukrainian refugees have essentially been invited to Ireland: all member states of the European Union have implemented the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) which granted Ukrainians permission to enter the EU and to temporarily work and live here. The TPD means that Ukrainians are allowed to work in Ireland just as any other EU citizen. Joining the workforce should enable refugees to integrate into the host society and of course also ensure that refugees support themselves.

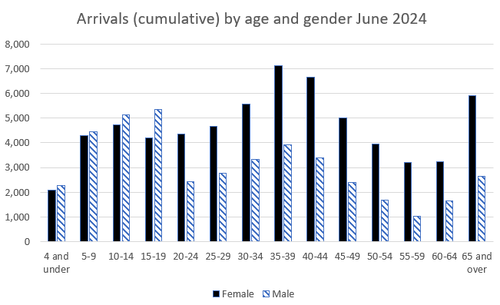

Ukrainian refugees in Ireland are disproportionately women with young children. Nearly a third of all Ukrainians are children and young adults (age groups 0-19); working age women (20-64) comprise more than a third of the entire Ukrainian population in Ireland. Especially numerous amongst adults are women aged between 30 and 45 (Chart 1). Ukrainian refugees are well educated with about half of the adults having at least an undergraduate degree. Of those refugees reporting a previous occupation, ‘Professionals’ was the largest category; craft workers and less skilled occupations were far fewer.

All of this means that Ukrainians are exactly the sort of people ‘deserving’ of temporary protection. However, they are also uniquely disadvantaged by four deeply entrenched Irish barriers to labour market participation.

First and most obvious is the housing crisis. Compared to Ukrainian refugees in other EU member states, few Ukrainians in Ireland have moved into the private rental sector. Because affordable accommodation is out of reach, nearly all Ukrainian refugees are still in supported housing. This often means hotels, which are in areas where suitable jobs are few. Furthermore, accommodation is defined as temporary, so refugees cannot commit to a long-term job. All too often, refugees who have found a job have to resign at short notice because they have been moved to other accommodation. The housing crisis thus restricts access to employment.

Secondly, for women with dependent children, childcare is a major issue. Despite the recent expansion of publicly funded childcare through the National Childcare Scheme (NCS) and Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) programme, childcare in Ireland remains expensive and in short supply. While many Ukrainian children are now enrolled in NCS and ECCE, accessing adequate childcare remains a common problem. By contrast, one real achievement has been the complete enrolment of Ukrainian children into Irish schools. Equally, another successful aspect of the Ukrainian experience has been the accelerated recognition of the qualifications of Ukrainian teachers, many of whom are now working in Irish schools. Nonetheless, the comparatively short Irish school hours, long school holidays and the assumption that young children need parental supervision, all mean that Ukrainian mothers face a novel constraint on their employment. As one refugee interviewee remarked: ‘I don’t know how Irish mothers have jobs’.

Thirdly, in Ireland a car is now often essential to have a job. According to the census, fully 63% of people who travel to work do so in a private car. This reliance on the private car is not just a rural issue, since even in Dublin people are more likely to travel to work by car than in many other European cities. Employment opportunities are limited for those without a car. This enforced car dependency is largely ignored in employment policy but poses a further limitation on integration through employment. Furthermore, most Ukrainian refugees are accustomed to accessing employment by public transport and are used to extensive public transport in the large cities. As one interviewee remarked, ‘Our cities have metros…’.

Finally, further education and training (as opposed to third level education) is under-developed in Ireland compared to many other European countries. Not only have traditional apprenticeships declined but crucially further education and re-retraining remains limited. Although Education and Training Boards have been successful in getting Ukrainian children into Irish schools, their provision of training (especially language training) for adults seems to have been rather weak. This is consistent with the under-development of further education and training in Ireland compared to many other European states.

It is useful to compare Ukrainian refugees with another group of recent immigrants who also had full access to the labour market: the large number of people from Poland and the other New Member States who arrived after 2004. Those new arrivals were well educated, relatively young and very few had dependents with them; they were prepared to take any job and move anywhere in order to gain a foothold in the labour market. For them Irish inefficiencies in housing, childcare, transport and training were of little relevance. By contrast, the very different demographic profile of Ukrainian refugees today means that they are disproportionately affected by these problems. For them, the Irish labour market is all too often not a welcoming space.

Chart: Ukrainian refugees in Ireland

Source: CSO, Arrivals from Ukraine in Ireland Series 13, Table 2.

https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/p-aui/arrivalsfromukraineinirelandseries13/

Derived from James Wickham, The labour market integration of Ukrainian refugees in Ireland: A report for DG Employment and Social Affairs (2023).

Professor James Wickham

James Wickham was Jean Monnet Professor of European Labour Market Studies and Professor in Sociology at Trinity College Dublin. He has published widely on employment, transport and migration in Ireland and Europe; he is the author of Gridlock: Dublin’s Transport Crisis and the Future of the City and co-author of New Mobilities in Europe: Polish Migration to Ireland post-2004. His book Unequal Europe: Social divisions and social cohesion in an old continent analysed the collapse of the European Social Model; his new text book European Societies (Routledge 2020) examines the structures of inequality in contemporary Europe. He is a former director of TASC.

Share: